The global digital infrastructure boom isn’t just about technology—it’s a high-stakes battle over land, energy, and power.

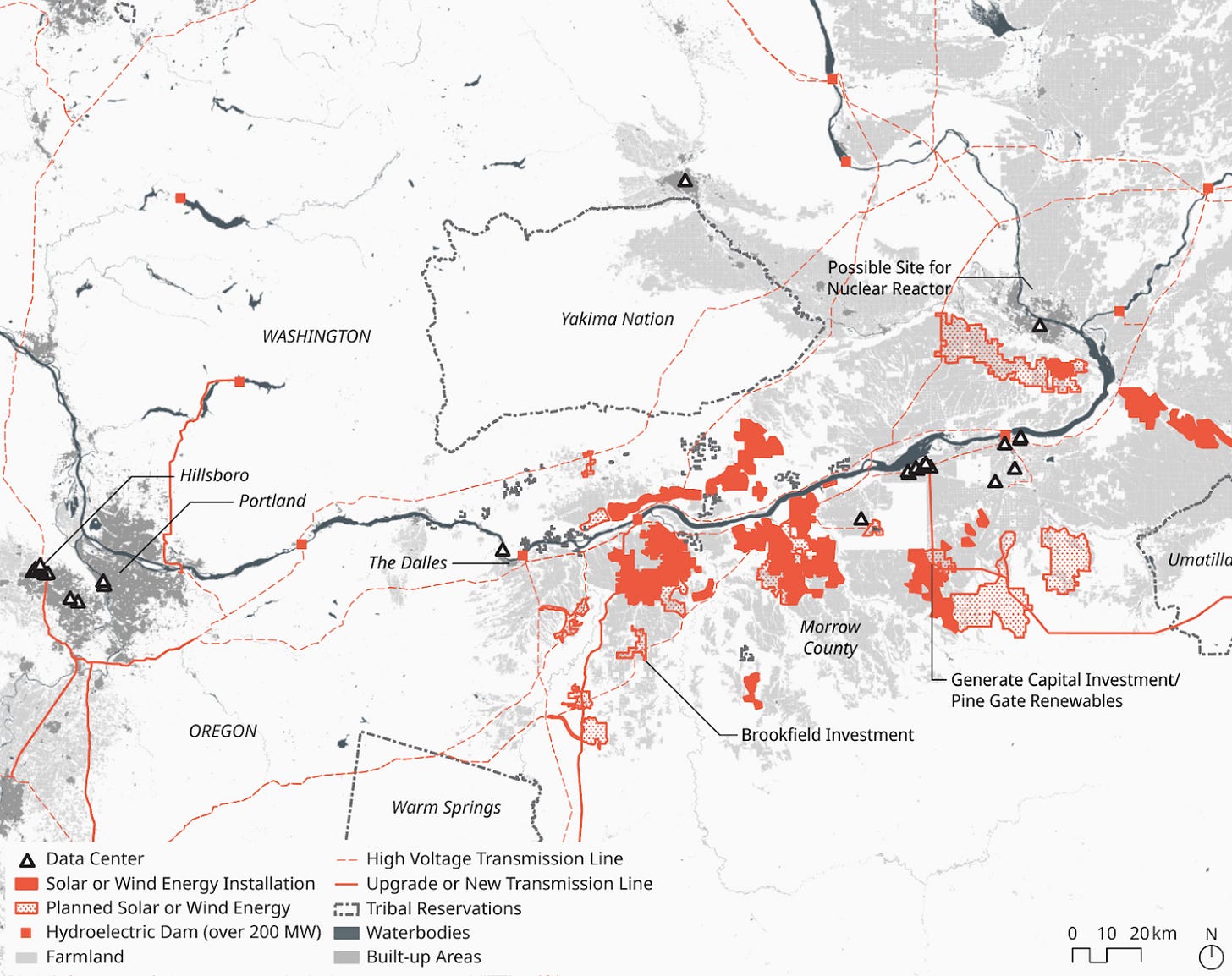

Last week, I wrote about Google’s data center expansion in The Dalles, Oregon, and its growing demand for water and energy. But The Dalles is just one piece of a much larger story unfolding across the Columbia River Basin. Amazon, too, has built out massive facilities, straining local infrastructure and reshaping the regional landscape. The Yakama Nation now finds itself in a legal standoff with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission over renewable projects encroaching on sensitive cultural sites. Every new data center ramps up the pressure to expand energy production, but make no mistake—this isn’t a benevolent green transition. It’s a race to sustain the insatiable power demands of AI-driven cloud infrastructure, forcing policymakers and utilities into uncomfortable (and sometimes very comfortable) decisions.

The Cost of Amazon’s Footprint

Amazon has perfected the art of getting what it wants. Over the past decade, Amazon has spent tens of billions of dollars expanding its data center empire across Morrow and Umatilla Counties, benefiting from a generous suite of tax breaks—$50 million annually, climbing to $76 million in 2022. And the incentives keep flowing. In 2023, the Port of Morrow unanimously approved another $1 billion in tax subsidies to support five more data centers, collectively valued at $12 billion. Despite the scale of investment, the economic benefits for local communities remain limited. But some officials involved in these negotiations have managed to benefit in other ways. Not long after Amazon’s arrival, local figures who had been brokering deals with the company acquired Inland Development Corp, a nonprofit fiber provider originally created to support government and healthcare services. In 2011, it expanded its operations to serve private businesses under a new subsidiary, Windwave Communications, while maintaining its nonprofit status.

As Amazon’s data centers multiplied, Windwave’s profits tripled between 2013 and 2017. Then, in 2016, its board members—who included a county commissioner and the port’s former director—sold the company to themselves. The details of the sale remain murky since Windwave’s finances were no longer public after the transaction. What’s clear is that these same officials were negotiating Amazon’s tax breaks at the time, while also setting themselves up for a windfall. Between 2016 and 2020, Amazon secured five tax deals under Oregon’s enterprise zone program, saving hundreds of millions in property taxes. By 2024, the Oregon Government Ethics Commission finally stepped in. Three former public officials settled an ethics complaint over their dealings, each paying a $2,000 fine—a small price to pay given the scale of the transactions involved.

Footprint of Existing and Proposed Green Energy Facilities Compared to the Portland Area and Nearby Tribal Areas in 2024

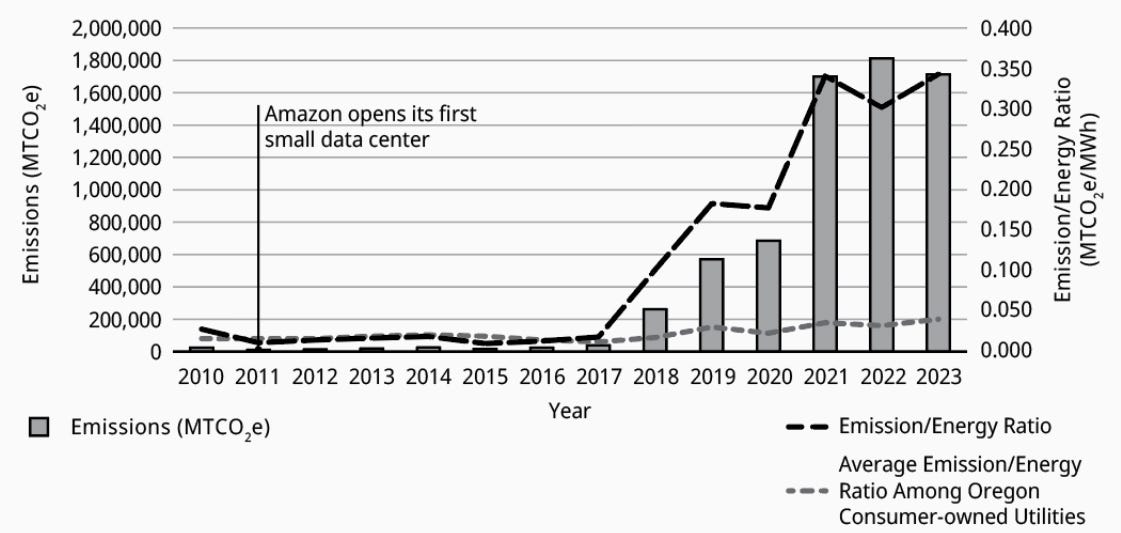

A Growing Carbon Footprint

With more data centers has come a surge in carbon emissions. Umatilla Electric Cooperative, which serves both Umatilla and Morrow Counties, has become the third-largest greenhouse gas emitter among all Oregon utilities. The reason? Amazon.

Back in 2011, before Amazon set up shop in the region, Umatilla Electric’s carbon emissions were just 10,600 tons. By 2022, that number had exploded to 1.8 million tons. The increase comes down to simple math: the cheap hydropower from the Bonneville Power Administration was already spoken for, so Umatilla Electric had to source additional power elsewhere. That has meant relying heavily on fossil fuels, including a nearby natural gas plant. Utilities across the region are now scrambling to adjust their projections. With AI-powered cloud services adding even more strain to the grid, Portland General Electric and two other major utilities have sharply raised their forecasts for data center energy demand. The Bonneville Power Administration now expects that by 2041, data centers in Oregon and Washington will require more than double the electricity they use today—an amount equivalent to the power consumption of one-third of all homes in both states.

Efforts to curb these emissions have been unsuccessful. In early 2023, a bill was introduced that would have required data centers and cryptocurrency miners to transition to renewable energy by 2040. Amazon, unsurprisingly, pushed back, spending $93,000 on lobbying in the first three months of the year alone. The company argued that the bill imposed clean energy mandates without offering incentives to build the necessary grid connections. The bill died in committee. Instead, lawmakers opted to extend tax breaks, sweetening the deal with new semiconductor incentives (more on this another time) and pushing the sunset date of Oregon’s enterprise zone program from 2025 to 2032. Transparency remains a recurring issue. Local officials often keep negotiations with tech companies under wraps, citing the need to protect proprietary information.

Carbon Emissions and Emissions/Energy Ratio for Umatilla Electric Cooperative 2010 to 2023

Renewables and the Reality Check

Despite its rising carbon footprint, Amazon has aggressively marketed its investments in renewable energy. These investments, however, are primarily about keeping the company’s own cloud empire running, not reducing the grid’s overall reliance on fossil fuels.

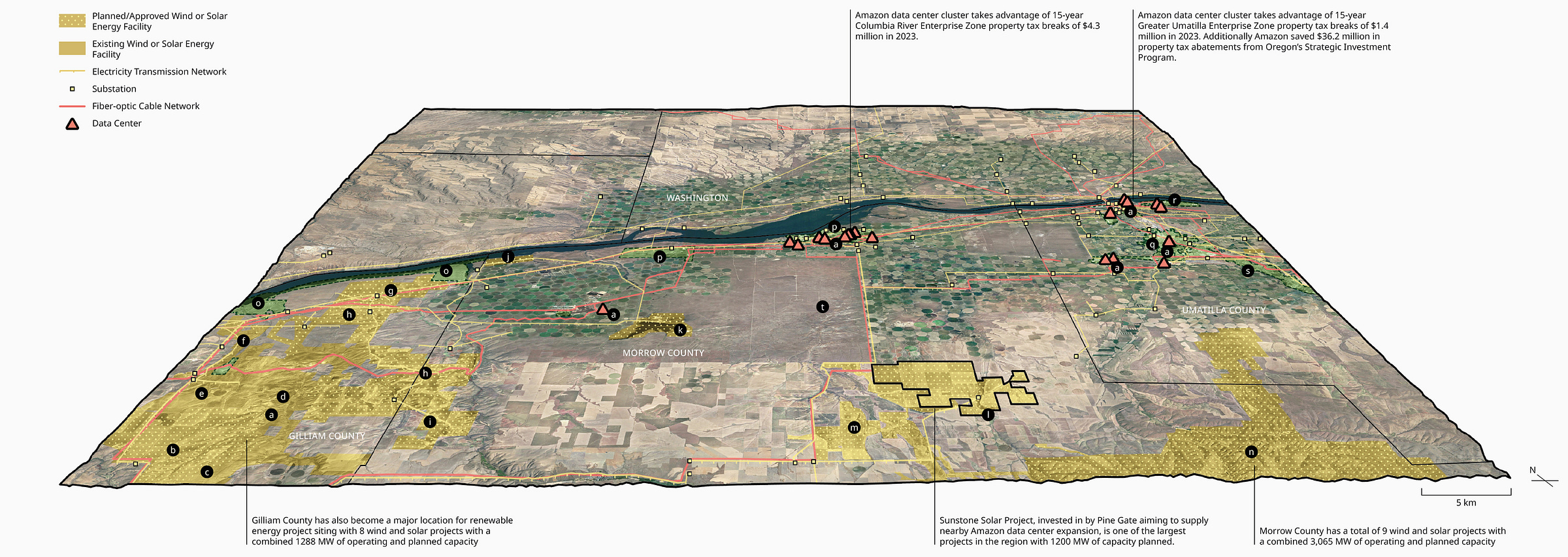

Take Pine Gate Renewables, for example. The company is backing the Sunstone Solar Project, a massive 1,200-megawatt solar farm in eastern Oregon, largely to power Amazon’s operations. The exhibit provided in the Sunstone Solar Project permitting documents notes:

Amazon which already operates four large data centers in Morrow County, recently announced an agreement with Morrow County to build six new data center facilities. … In addition, existing development and food processing plants have increased demand for energy in the region. This growth in recent years has had a measurable impact to utility services, with the UEC reporting industrial power consumption is up 266 percent since 2016. … These economic developments in Morrow County require power; therefore, the construction of clean energy projects like the Facility support this economic development.

Meanwhile, Avangrid, a subsidiary of the Spanish multinational Iberdrola, has inked deals with Amazon, Meta, and other cloud giants for wind power. Avangrid’s Leaning Juniper IIA wind farm nearby claims to produce enough energy to power 22,800 homes—but that electricity is largely destined for the expansion of Amazon’s computing power, not the local community—or at least will not offset existing emissions under a net-zero framework.

Even with these investments, there’s simply not enough renewable energy to meet Amazon’s needs. Enter a new solution: fuel cells powered by tapping natural gas from the Gas Transmission Northwest pipeline. In a move branded as “innovative,” Amazon has proposed installing these fuel cells at three of its data centers. The catch? They would emit 250,000 tons of carbon dioxide annually. More importantly, they would allow Amazon to bypass grid constraints, ensuring a more reliable power supply for its cloud infrastructure while sidestepping broader efforts to transition to clean energy.

Territoriality of the Morrow and Umatilla County data center cluster and renewable energy infrastructure expansion

Who’s in Control?

Cloud capital’s deep ties to energy infrastructure show how network power is reshaping territorial governance. It’s no longer local utilities or governments setting the terms—it's tech monopolies steering the conversation. Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are not only demanding more power but also influencing how that power is produced, transmitted, and subsidized. This goes beyond ESG commitments; renewables can be deployed faster than carbon-intensive plants and benefit from state incentives. Yet, despite subsidies fueling wind and solar projects in the Columbia River Watershed, the expansion of long-range transmission lines has sparked fierce opposition from environmentalists, farmers, and property owners concerned about ecosystem disruption.

But this isn’t just about corporate dominance—it’s also about financial networks driving infrastructure expansion through capital flows untethered from the localized nuances of environmental sustainability. Public pension funds, including California’s State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) and Canada’s Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan (HOOPP), have poured capital into renewable energy projects tied to data center expansion. Generate Capital, a major investor in renewables including Pine Gate Renewables, even had ties to the Biden administration, as its co-founder was tapped to run the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office. These links reveal just how embedded cloud infrastructure has become in state-backed financial systems.

Cloud capital’s reliance on fast-tracked renewables legitimizes the techno-state by tying socialized finance, including pension funds, to its expansion. This shift subordinates local utilities and planning to the needs of tech giants, whose power extends beyond economics to legal, political, and engineering networks. Yet, this dominance fuels environmental injustice, as cloud capital’s resource demands increasingly displace local needs.1 While Amazon has taken steps to soften its image—like using recycled water from its data centers for agriculture in Umatilla County, that doesn’t change the fundamental question: would these communities be better off if Amazon simply paid its fair share in taxes rather than offering these selective benefits?

Meanwhile, data centers continue to provide relatively few jobs, which was the original rationale for Oregon’s tax incentive programs in the first place. For now, tax revenue for Oregon’s schools is justification enough. At the end of the day, the cloud isn’t some weightless, ephemeral system. It’s a massive, resource-intensive infrastructure that reshapes landscapes, redirects public resources, and locks local economies into a tech-driven energy grid.

In the future, I will take a closer look at semiconductor manufacturing—the upstream production of the chips that power the servers in data centers—as well as the financial relationships and dependencies of regional economies on this industry. Thanks for reading and stay tuned!

References

Mulvaney, Dustin. 2024. “Embodied Energy Injustice and the Political Ecology of Solar Power.” Energy Research & Social Science 115 (103607): 103607. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2024.103607